The word entrepreneur has always had too much of a business-ey ring for my liking. Despite its connection with innovation and creativity, it more conjures up images of suits and multi million-dollar deals than it does artists, musicians, poets—People I admired growing up. Needless to say, I never thought of myself as an entrepreneur. I always believed the profession and lifestyle to be far removed from anything I’d ever do, let alone be interested in. That all changed when I moved to Vietnam.

It wasn’t something I noticed right off the bat: this idea of how everyone here’s an entrepreneur. For the first six months in Saigon, I never thought about it at all, given that I was more preoccupied with finding my feet in an absolute madhouse of a city. But overtime you find your footing, the constant blare of motorbike horns starts to sound a little less frightening, a little less like it’s aimed directly at you. You’re finally able to stop and pause once in a while, look around and try to make sense of the streets that wind into an intricate web of alleyways, going everywhere, going nowhere. You might even begin to grasp a few words of the language so something that sounded so alien, so foreign, finally starts to click. When you muster the courage to greet a neighbour or a stranger you may be pleasantly surprised when they reply with a smile and greeting of their own. And so Vietnam unravels, evermore mysterious but somehow familiar, too. It was around then this idea first came to me.

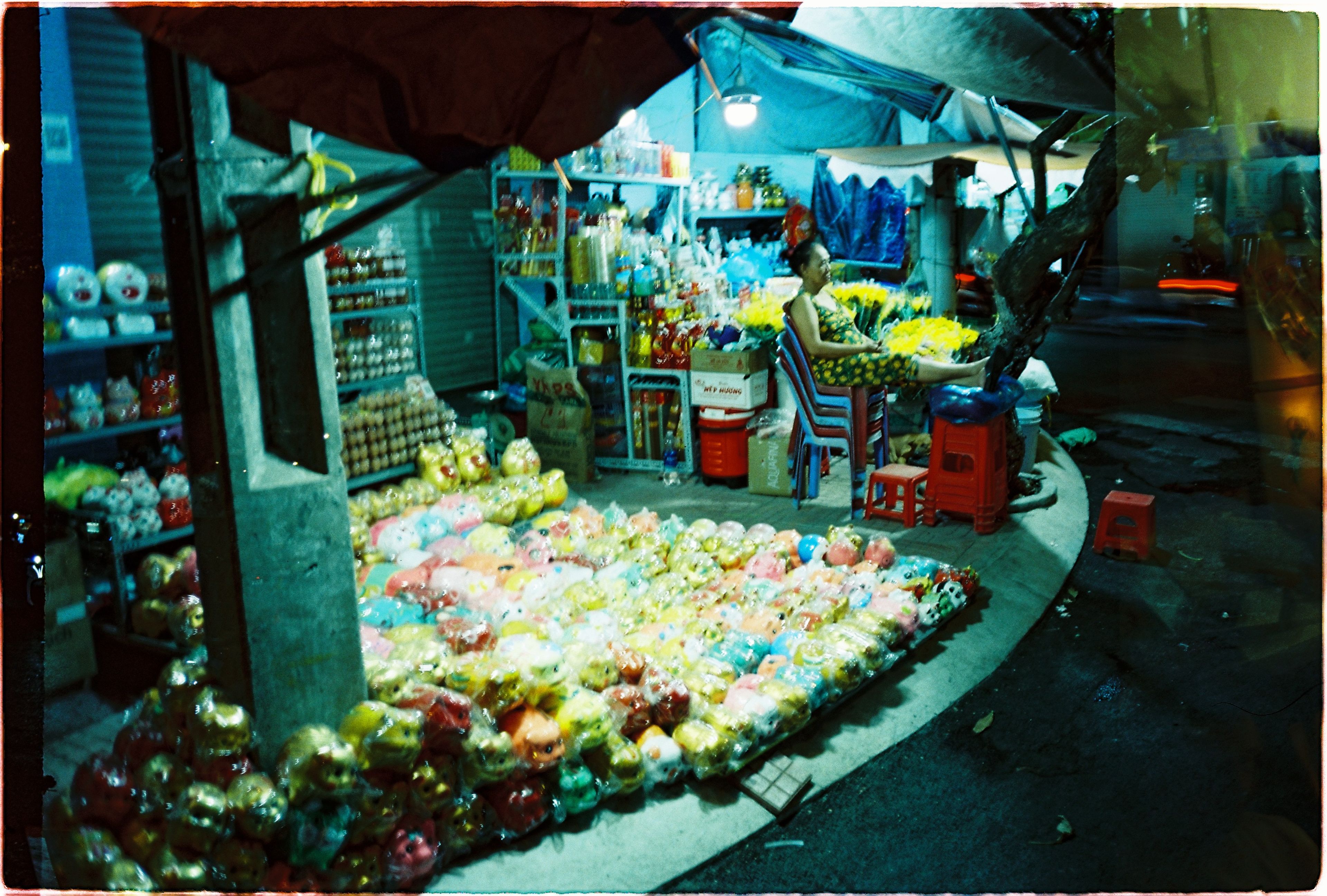

No matter where you are in Vietnam, you’re always going to find a street food joint or juice stall run by a family or a single person. They’re everywhere. On every street, every corner, whether they’re selling a bowl of Phở, a Bánh mì, or a cup of sweet, citrusy Trà tắc. These street stalls are vital to the country, providing families with an income, people with sustenance, and serving as a reminder to tourists and expats why this country is so great in the first place—How could it not be, when food & drinks are so accessible, so affordable, so delicious? Again, the majority of these stalls are run by families and individuals: entrepreneurs who’ve decided they can build something from scratch, that they don’t need to sign away their sanity working twelve-hour days as was common for me to see growing up in Tokyo. It’s impossible not to commend this kind of a do-it-yourself attitude. There’s a real willingness among the Vietnamese to give things a shot and if it works out, great. If it doesn’t, well, you tried.

During my two years in Saigon, I’ve come across all sorts of entrepreneurs. Mechanics, masseuses, martial arts coaches, electricians, florists, cafe owners, cooks, chemists, cleaners, cigarette retailers, artisans, craftsmen, painters, drivers, tour guides, teachers—If you can name it, there’s a likelihood someone in Vietnam’s started a business out of it, whether that be from a humble street cart, out of their living room, or, if they’re real lucky, in an actual building. Some of my favourite entrepreneurs so far have been university students selling ice-cold matcha drinks on the side of the road. They had nothing to rely on but their will, a cooler box, and a cheap coffee machine. Then there’s been an old man selling hand-crafted, hand-painted masks from the back of his bicycle. I always caught him riding his bicycle on my way to work in the afternoon. One day even came to a traffic stop beside him, and giving a nod, he smiled back a toothy grin before pedalling on his merry way.

No matter where you live in the city, you also get to know a few neighbourhood entrepreneurs. Back when I lived in Đa Kao there was a bowlegged man who ran a cơm tấm joint a short walk from my house. He was a pleasant man, had a peace about him, something of a modern-day Buddha in how he was always grilling ribs on a busted up grill while Saigon’s traffic rumbled all around. He was never bothered, smoked cigs sometimes, other times didn’t, and when the ribs were cooked he’d hobble over to a shack that doubled as a kitchen and display booth. I’ve since moved from Đa Kao to an area in Bình Thạnh, and my neighbourhood entrepreneurs are three women: one who sells bananas and rice, another all kinds of juices, and the third a middle-aged lady selling some of the best goddamn Hủ tiếu I’ve had in the city. She always laughs when I make my order, says thank you after I’ve paid and hands me a plastic bag filled with noodles, soup, several kinds of meat, and the customary lime, chilli, and herb trio.

Having lived in a country with such a get-up-and-go mentality for two years now, perhaps the attitude has rubbed off a little. The entrepreneur no longer seems so far removed, no longer has to be that special, rare businessperson who changes the world through a company or an idea. In Vietnam, everyone’s an entrepreneur. Something of a Vietnamese dream, really. It’s part of the reason why District 0 came about, and why the thought of starting it didn’t feel as daunting or impossible. It’s because of Vietnam—Thanks to Vietnam. Though I had my reservations, the more I spoke to Garrett and Aidan about the idea, the more it became apparent that we could and should do this. After all, why not? I’ve always wanted to be an author, and publishing my first novel and finishing my second remain some of my biggest goals. Now, though, building District 0 has become a part of those dreams. And who knows? Maybe one day you’ll call me an entrepreneur.