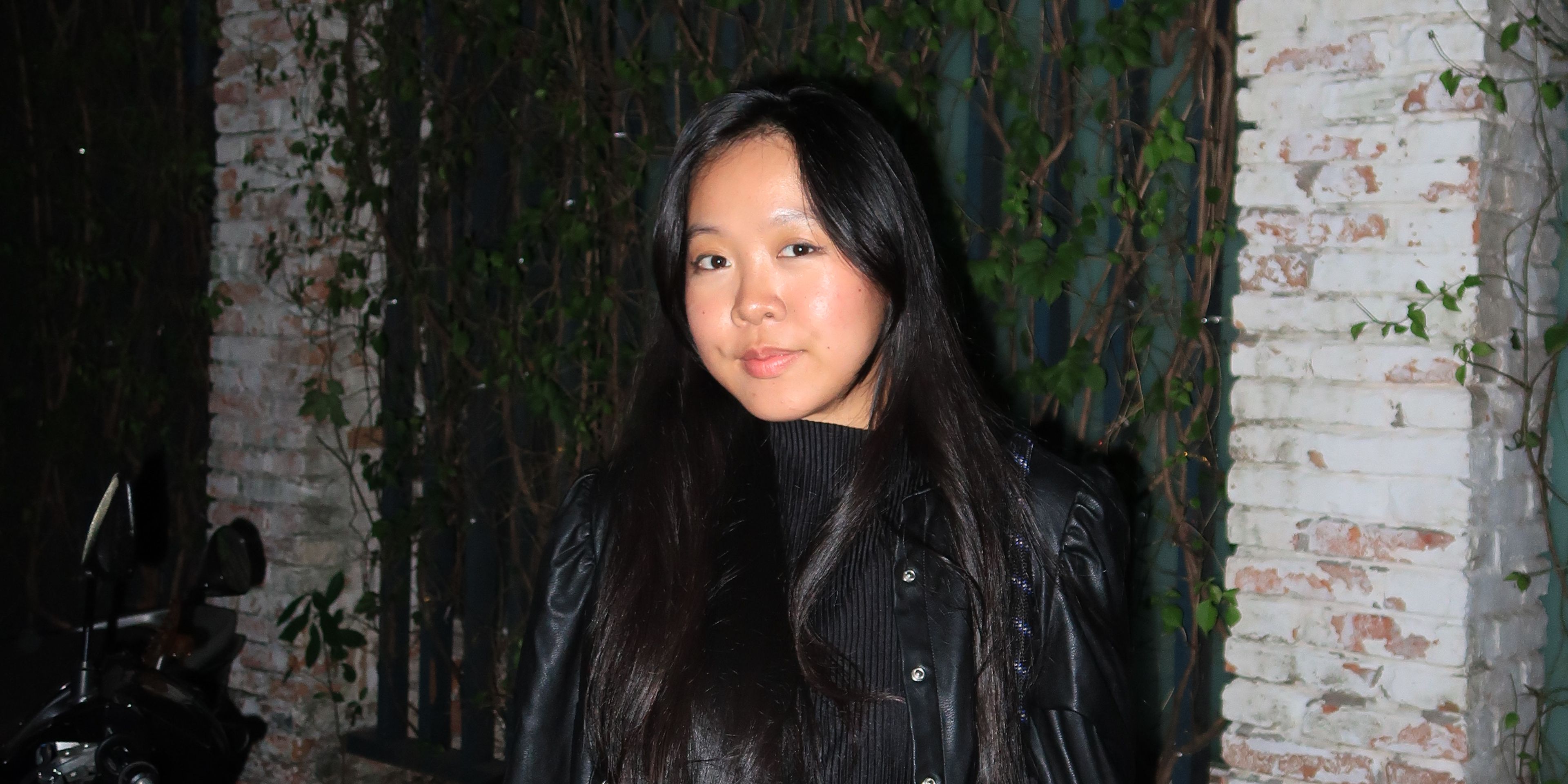

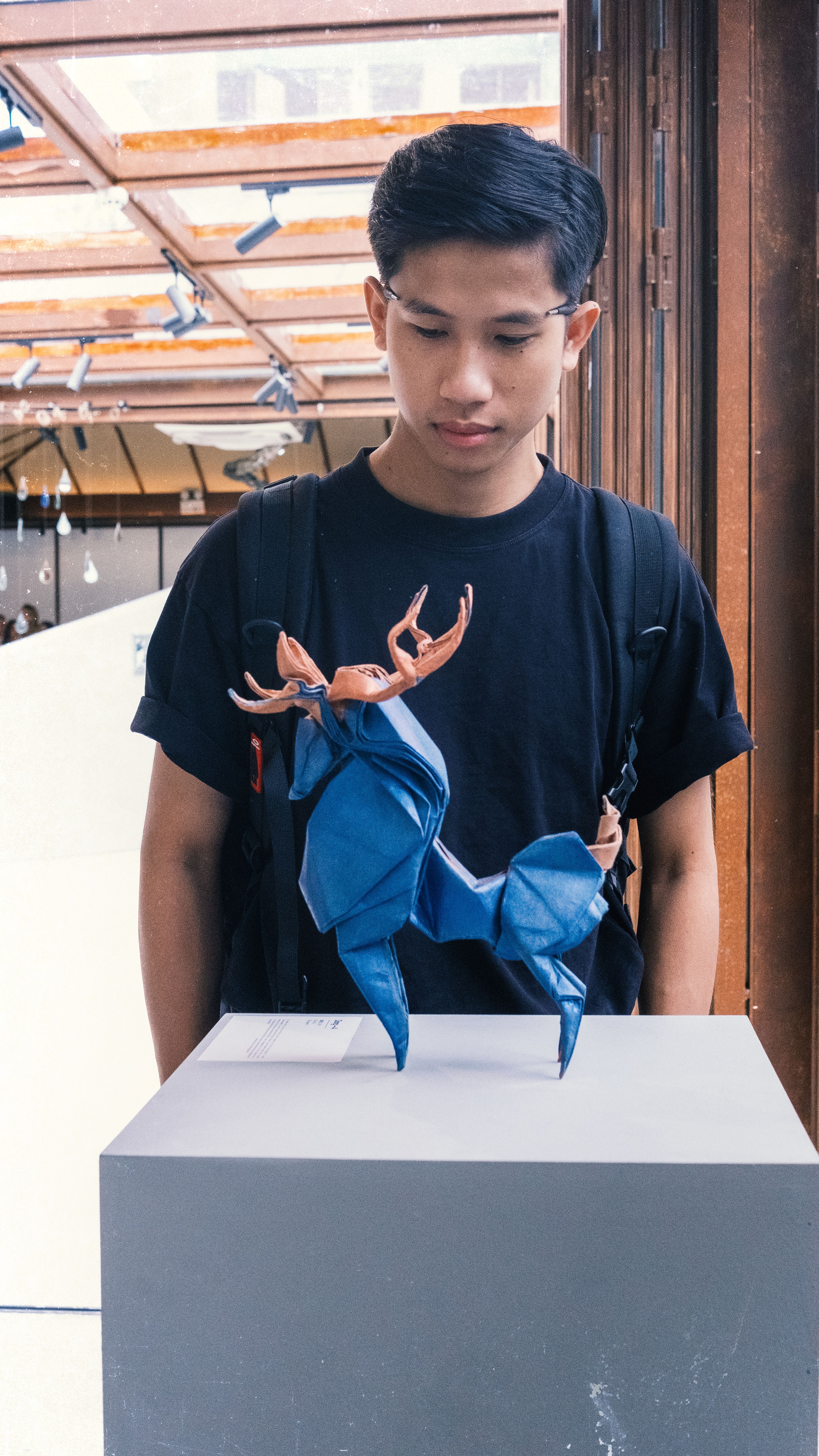

How does one turn a piece of paper into a reposed lion, a wasp suspended in the air, or a towering monster? Practice. One fold at a time. Slowly. Gently. With Zen-like precision and ease. Paper can be torn, burned, destroyed, but when thoughtfully cared for and consciously molded, it becomes symbolic. Evolved. Elevated. Everlasting. The first time I encountered this work was at the LÔCÔ Art Market last year. I had never seen origami like it before and felt compelled to know more about who was behind it all. Months later, I finally met him, a twenty-eight-year-old contemporary artist, Dong—4. The number four after his name, he tells me, is a secret.

“MacLean?”

I had been standing on the side of the street for a few minutes, taking in my surroundings. I turned around and couldn’t help but laugh. I hadn’t heard my last name in a long time.

“Dong?”

His yellow Brixton glowed under the street lamp.

“Hop on. I’ll take you from here.”

Dong’s someone you trust immediately, at least I did. I jumped on the back of his bike, now holding my backpack in front of me, and he whipped his bike around, leaving the glowing street to disappear into the darkness. Straight. Up. Down. Left. Right. Left. Straight. We snaked our way over a bridge, around the water bank, and underneath the hanging linen. I could see Landmark 81 in the distance so I knew we were still in Saigon, but this was new territory for me.

In seven years of living in the city, I’d never been to Bình Quới before, let alone this hidden patch of land. Hours later, when Dong and I had dinner at the ốc spot back down the glowing street where we came from, he told me the owner was the one that offered him a room over here two years back. It’s no wonder Dong took up the opportunity then. It’s quiet. Right by the water. Serene. The perfect setting to create. Moments later, we parked and entered Dong’s home and studio where he does most of his work.

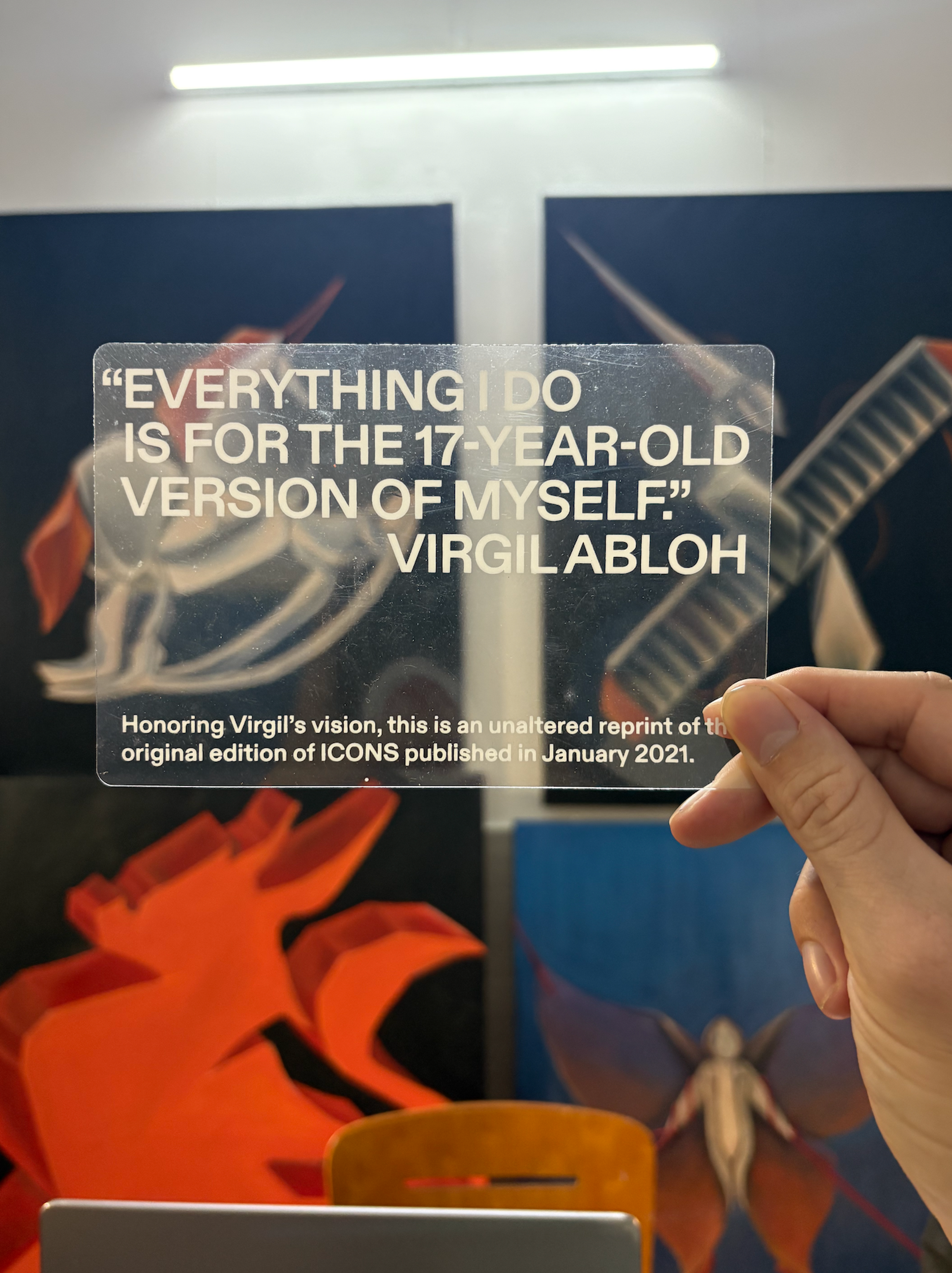

The lion was there on his desk, waiting, still in its reposed stature. The wasp, too, except not suspended in the air, but tethered to the wall. The towering monster stood behind his work desk. Canvas after canvas stacked up, lining both walls. A moth. A rocking-horse. Vietnam’s national bird, a Chim Lạc. Two desk lamps lit the room. Tons of match box cars, collectibles, and an occasionally used camera was placed near a section dedicated to acrylic paint tubes, spray paint cans, and staplers. On his table, a laptop and tons of books including a bright neon green one with a black Kirin—a mythical beast of good fortune—standing guard atop the text, ICONS by legendary artist and designer Virgil Abloh. Inside a quote reads, “Everything I do is for the 17-year-old version of myself.”

I take a seat and pull out my laptop. Dong is still standing, pacing a bit, presumably still perplexed as to why I came all the way out here at night on the weekend to meet him. It’d been months since I’d seen his work, and since then my curiosity remained, and had even grown. Could it be true for Dong as it was for Virgil, does he do everything for his teenage self, or is there something else that drives him?

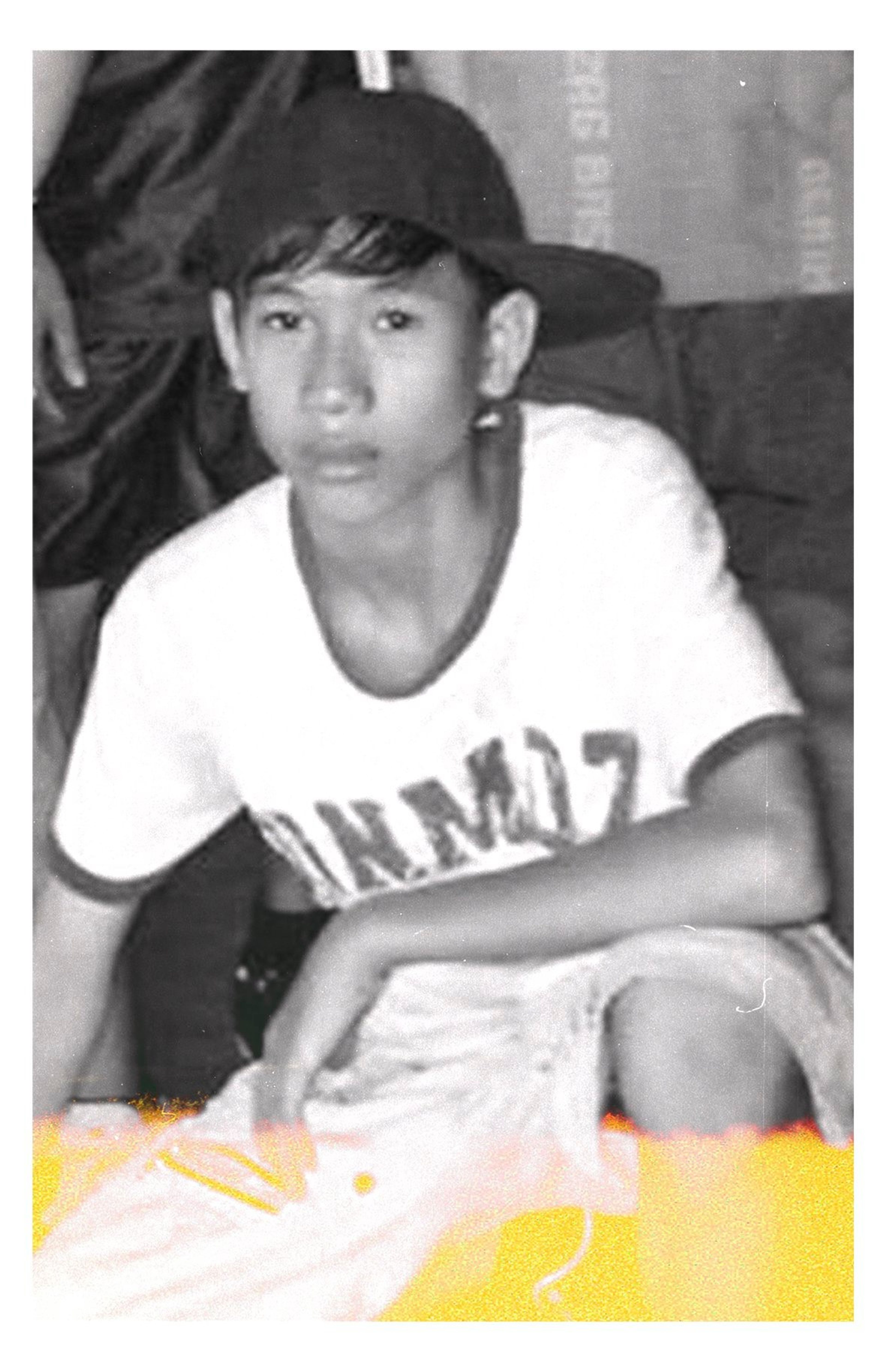

Dong was born in Bình Phước. Before he got into origami, he first fell in love with break dancing. At the end of secondary school he joined a hip hop dance crew with his friends. They performed all over his hometown favoring mostly old school beats. Think Wu-Tang Clan, Mobb Deep, and Mos Def. That’s why Dong described his creative mind as a split between hip hop dance and origami. Dancing provides him with that energetic feeling. Origami gives him that Zen. This can be explained in part by the fact that Dong picked up origami around the same time he joined the hip hop dance crew. Thus, the yin and yang of Dong—subtle and in constant motion throughout our chat, yet still friendly and at ease, with a smile on his face.

Dong is a self-taught artist. He first learned how to fold by falling down a YouTube rabbit hole of origami videos in 2011. Video after video, model after model, day after day, Dong soaked up as much as he could. He said there was a period in high school, about roughly three years, where he would wake up at 5am, fold an origami, then go to school, and afterward practice dance with his friends. Eat. Sleep. Repeat. Not too long after he started, Dong submitted his own designs to the Origami Tanteidan International Convention. Every year they curate origami artists from around the world. The first year, he did a goldfish, then the following year a rhinoceros, and in the third and final year a cardinal bird.

All his own sketches include neat, numbered instructions on how to replicate his designs. Grinning with a cigarette hanging off his lip, he sprung from his chair to the corner of the studio and started grabbing books off the shelf. These were from over a decade ago. It appears his teenage self and his current self both have a love for animals so I asked, why animals? “It’s not just an animal,” he said. “The animal can represent more than just what it is. Like the spirit of something. An icon.” I look back at the word ICONS on the green spine of Virgil’s book. Makes sense. Each animal does represent something more than it is. Dong was born in 1997 marking the Year of the Buffalo in Vietnamese culture. What does the spirit of the buffalo represent? Steady discipline. Powerful patience. Stillness in motion. In other words, what is required of an artist over time.

Near the end of high school, Dong did his first few shows. The first was with a group of friends in District 7 at the Saigon Exhibition and Convention Center (SECC). It was a simple exhibition of his origami. The second was with a group of artists who’d been invited to Japan from all over the world. Afterwards, he made the move to Saigon in 2015 to complete his degree in design at Nguyễn Tất Thành University. At the very end of college, he did another exhibition, Nếp Gấp, a dual display in Saigon and Hoi An. Upon graduating, Dong worked as a freelance artist for two years before working in an advertising agency. The agency life is demanding, moving at a relentless pace to meet clients demands. Dong worked there for four years, and although he didn’t like it enough to continue he says he learned a lot from his experience.

All that said, in March 2025, Dong decided to quit and work full time as an independent artist. A couple months later he had his own art on display at the LÔCÔ Art Market in District 2. That is where I first saw his hand-made creations in the wild—a reposed lion, a wasp suspended in the air, and a towering McDonald’s branded monster holding a rooster. In the time between seeing Dong’s work and finally having our conversation, I learned that he experienced another first since quitting corporate life: his first solo trip. Given that it was his first time traveling solo, he went big—a bike ride across Vietnam. Just him, his iron steed, and three weeks to explore. Ho Chi Minh City. Da Lat. Da Nang. Hanoi. Up. Down. Left. Right. Over many bridges. Around many lakes. Through many tunnels. Pure freedom on the road.

As I’ve written before, going on a bike ride can be a form of meditation. A bike ride across an entire nation then, can be likened to an extended retreat. Dong wasn’t escaping from life however he was escaping to it. Enjoying the ride. Relishing each sunrise. Appreciating each sunset. Taking in all walks of life along the way. Noticing the intricacies. Being in contact with it all. Each scene. Each turn. Each place. As Robert Pirsig wrote in his book, The Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, "On a cycle the frame is gone. You're completely in contact with it all. You're in the scene, not just watching it anymore, and the sense of presence is overwhelming." Such a trip can change how you view things. It can make you reflect on your past, envision your future, and most importantly, center you in the present. In other words, it makes you feel alive.

One part of the trip that stood out to Dong was the very first night. He left Saigon near midnight, aiming straight for Da Lat. Hours later, at 2 a.m., he was lost and alone in one of the last places you’d want to find yourself—a graveyard. When I heard that, it struck me as fitting. Months after leaving his job and declaring himself an independent artist, Dong found himself face to face with a reminder. Graveyards, like animals, represent more than what they are. A graveyard is symbolic of the fact that while art may be long, life is inevitably short. As such, the sense of presence inside a graveyard can be overwhelming. Perhaps in a roundabout way, that trip elevated his appreciation of his time, deepened his gratitude for his work, and sharpened his vision for his future self. By the time he returned to his home weeks later in July, his taste for the road now satiated, Dong decided he didn’t want to only fold origami. He wanted to expand his limits inside the realm of contemporary art.

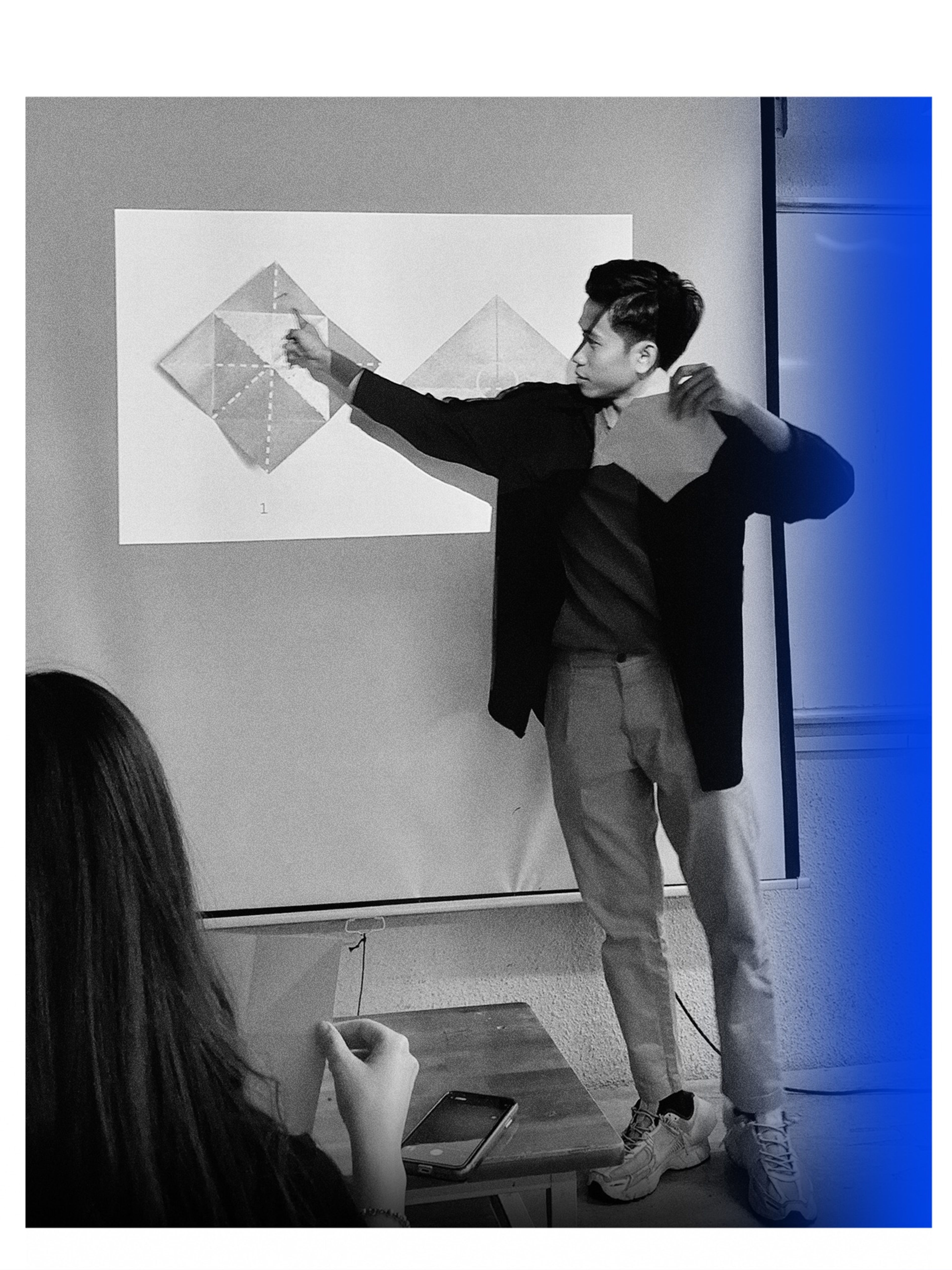

For the past year, he’s done just that. He’s been selling pieces to various buyers as well as doing commissioned work for clients. He’s also continued to put his work on display at exhibitions like Dela Sol, but after talking to him I came to find out his main focus right now is hosting workshops. Over the course of a few hours Dong teaches groups of 15-20 people, showcasing his skills and providing insight into how he sees things to others. He’s collaborated with a multitude of brands including Louis Vuitton, Kenzo Paris, FPT, Sun Life, Nest AIA, and Uniqlo. Dong also hinted at a bigger project where he’s going to be able to get back on his yellow Brixton and hit the road again, touring around Vietnam while hosting workshops in nearly a dozen cities.

At the end of our chat, when we sat at an ốc restaurant with bellies full of cold beer, delicious snails, and seafood fried rice, we finally got to Dong’s why—as in why does he do what he does? He thinks for a moment, a few motorbikes whizz by behind him, and says it’s simple. “I want to design and create for myself. I try to do my best, learn, and explore new things.” Hearing his answer I referred back to the quote inside the neon green book protected by the black Kirin on his desk, ICONS by Virgil Abloh. I asked him if it was the same for him as it was for Virgil. Close, but not quite.

Dong thinks about the future more than he does the past. “I want my artwork to become iconic. I want people to see my work and see me,” he says. He added that while many people want to create something beautiful, and he admits when he first started that’s what drove him too, but that’s not what does now. “My goal is not to create beauty, but to create something that is myself.” If what Dong said is true that each animal represents more than what it is, then Dong’s work represents more than what it is too. Every time you see Dong’s work, you see him, his why, his truth. And the truth is this: not striving for beauty, but rather working to stay true to one self, stay true to how you see the world, and stay true to your craft through discipline, patience, and stillness becomes something beyond beauty. Iconic.

Follow Dong—4 on Instagram and Facebook