Not many cafes stick out from the street quite like Cokernut Cafe in District 1. It has this distinctive orangish facade that catches your eye when you drive by. I stopped by recently thanks to a recommendation from Đức at Adau Kitchen. He said it’s the best cafe in the city. After spending a bit of time there — drinking coffee, eating cookies, and writing — I think I now understand why. Simply put, the place is great. What I didn’t expect though was the rabbit hole I would fall into after noticing what appeared to be the main character on the wall.

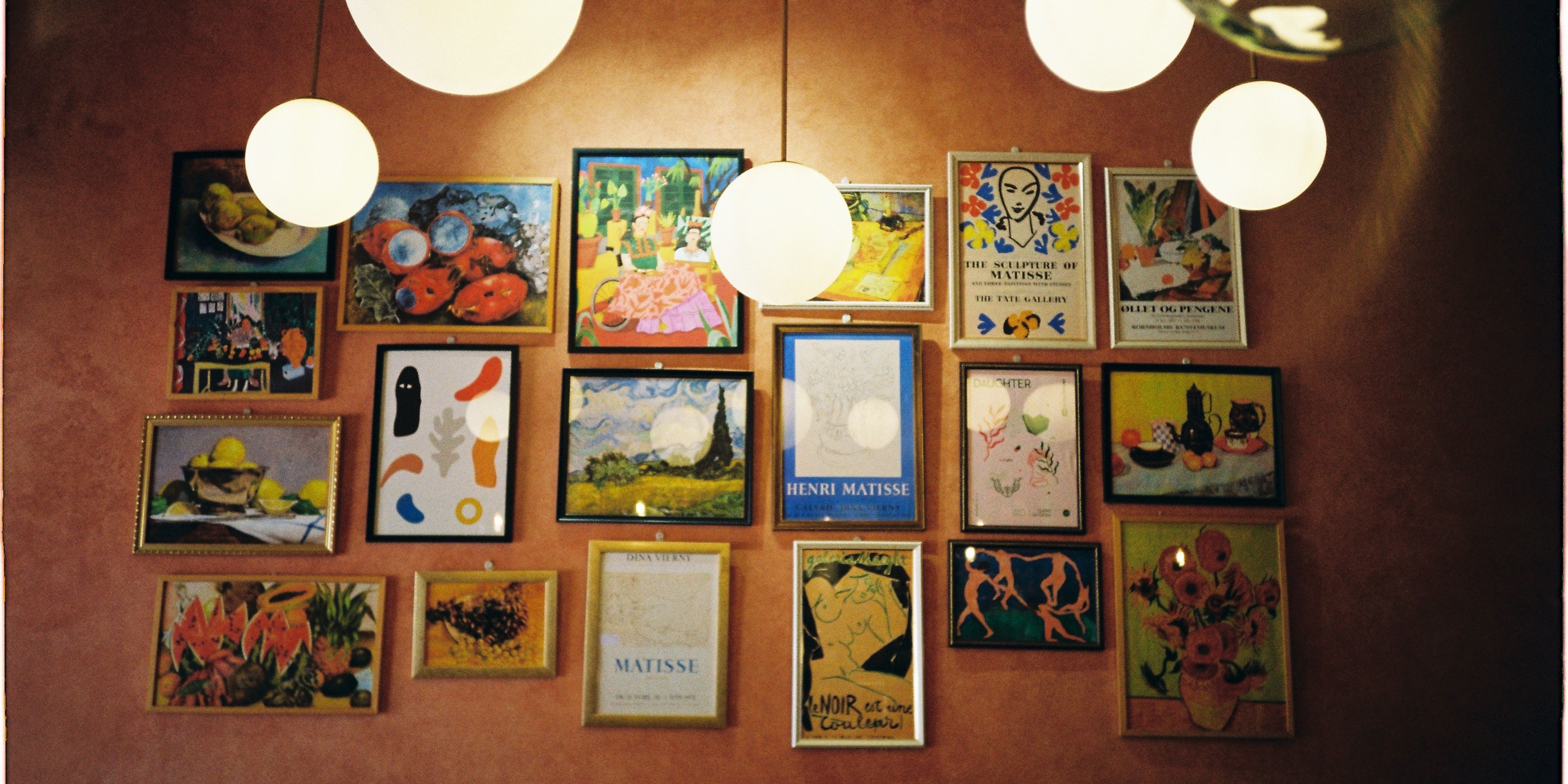

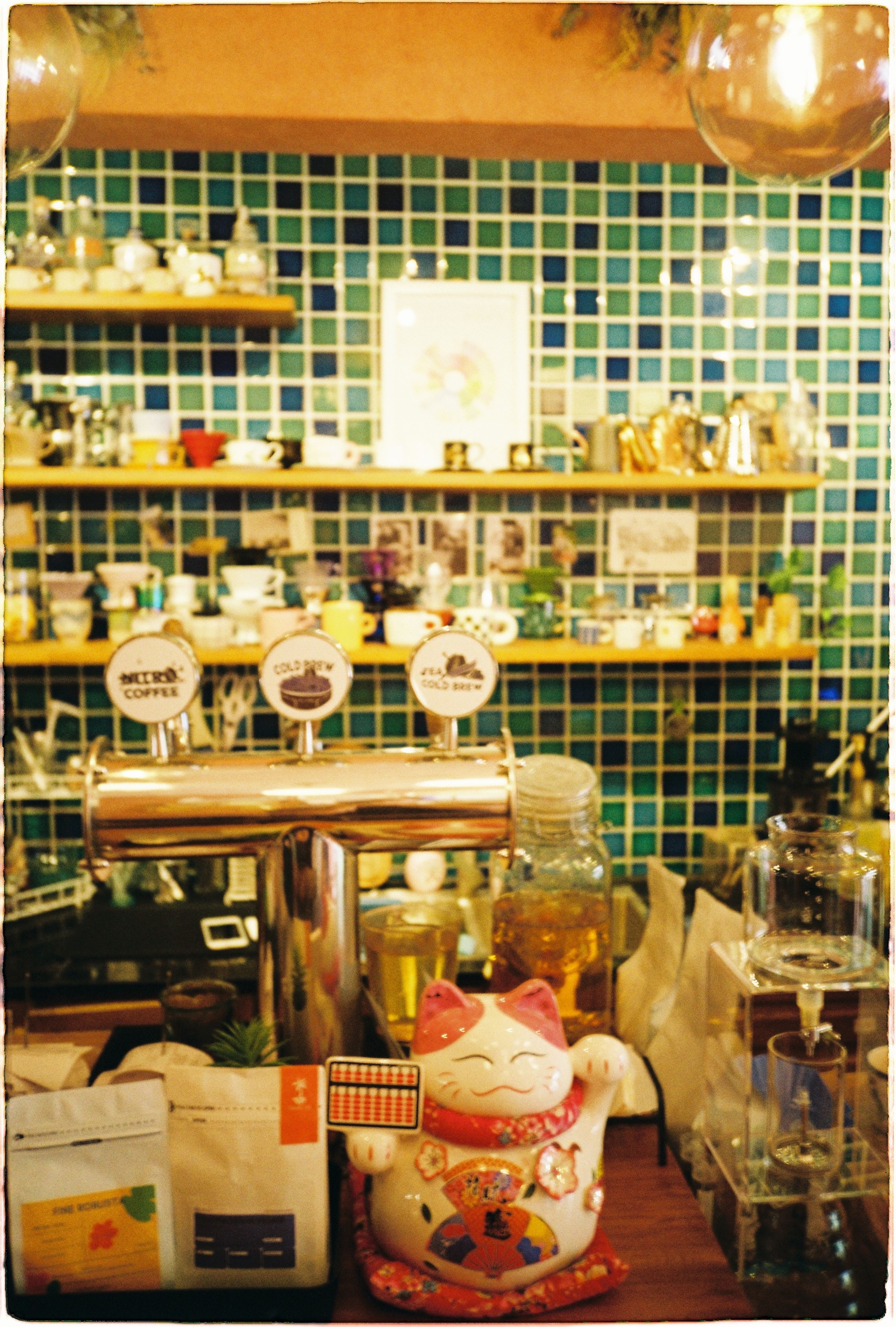

Unlike Bluish, where one hue dominates the space, Cokernut Cafe bursts with color. There’s a color wheel hanging behind the counter. Coffee mugs and glasses of all sorts of shades. A blue and green backsplash. A half-finished Rubik’s cube behind the register. Even the power strip connected to my computer features brown, red, yellow, blue, green and black sockets. But it’s the other wall that grabs my attention. Painted orange like the exterior, its artwork features what appears to be the main character here: Henri Matisse.

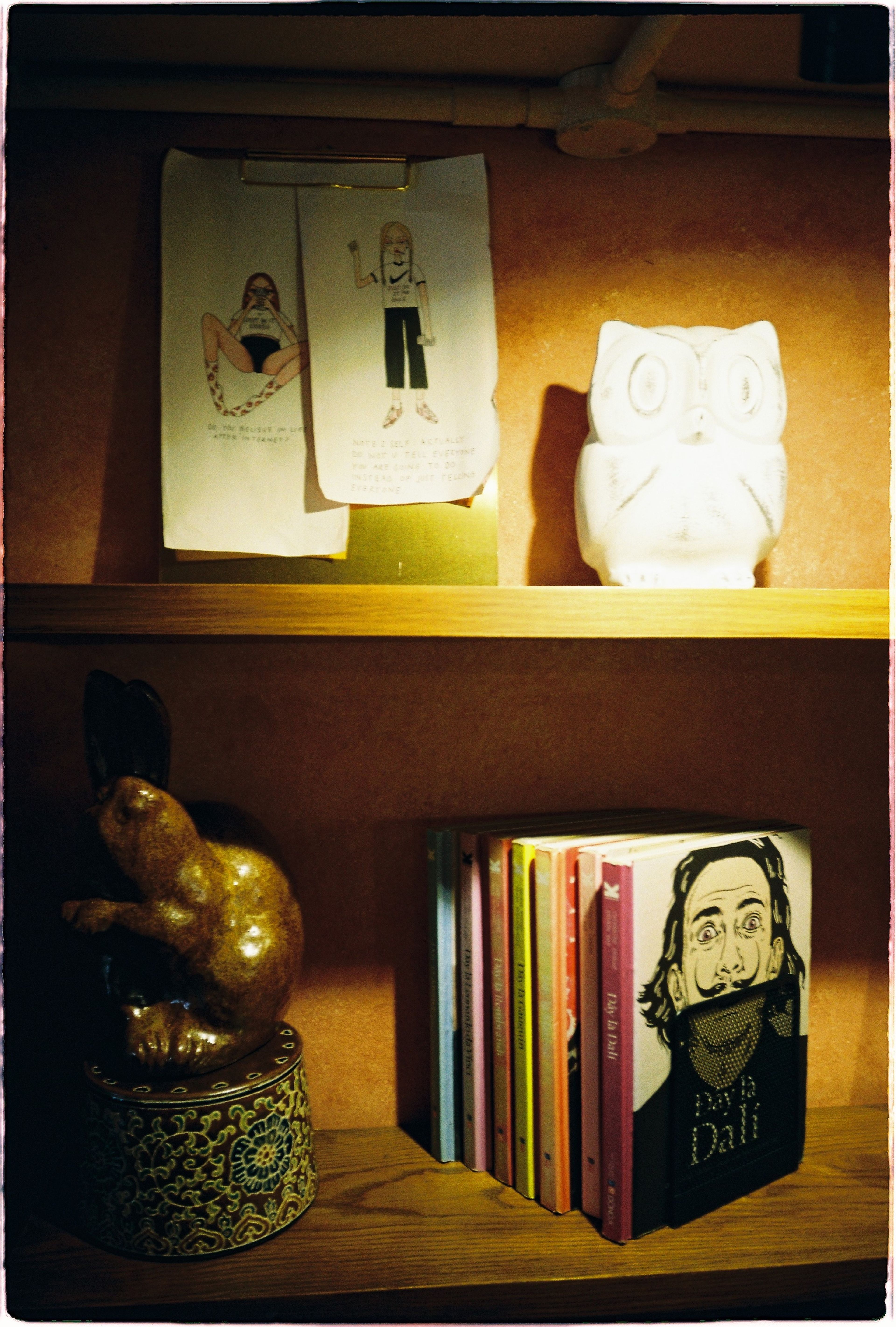

Besides Matisse, Van Gogh’s up there too. There are also lots of art books scattered around including one with a cover of Salvador Dali’s wondrous eyes watching me drink, eat, and type. Every time I looked up from my computer, it’s like his stare was telling me, “Look! Look! Don’t you see? Don’t you understand the message?” So I looked around and I noticed Matisse’s name on the wall more than once. I began to wonder who he was and what I could learn from him. So in another moment, fueled by coconut coffee and chocolate chip cookies, down the rabbit hole I went.

It started with a harmless Google search. For those, like myself, who didn’t pay attention during art history class, Matisse is an artist from France and is one of the most influential painters of the 20th century. Between 1900 and 1905 he received notoriety for his bold use of color which subsequently pioneered the Fauvism art movement. One of his most famous paintings is called The Dance which features five figures holding arms and dancing around in a circle. I came to learn that it was praised for its symbolism of unity, joy, and movement. The Dance was symbolic of the essence of life itself. A copy also hangs on the wall at Cokernut. I took a sip of coffee and started looking up other famous pieces by Matisse. Dali, still staring, waiting.

I found the Red Room, Blue Nude, Woman in a Hat, and then one that caught my eye: Icarus. The one from Greek mythology who flew too close to the sun, melted his wings made of wax, fell from the sky, and drowned. This picture though. I know this one. How do I know this one? I’ve seen this before. Where have I seen this before? That looks just like the cover of a book I once read but didn’t finish. The Body Keeps The Score by Bessel Van Der Kolk, M.D. Yes, this is the one I’ve seen before. I look up back at the wall at Cokernut, Icarus is not there. But I’m too far down the Matisse rabbit hole now with a dozen tabs or so open. There’s no stopping now. I guess I didn’t consider how in the world I was to get out again.

Recalling Matisse's rendition of Icarus on the cover of the Body Keeps the Score, I started thinking about one of the book’s main ideas: trauma is not purely psychological, it’s physical. Trauma isn’t just something that happens in the mind, it lives in the body. Trauma doesn’t just rewire your brain and fragment your memory, it disconnects you from feeling at home in your own skin. Because trauma is stored in the body, Kolk’s research has advocated for body-centered therapy methods. Methods that go beyond just talking about your feelings and turn you into a participant in the process rather than just a patient. One of such is the physical act of making art. Art is how humans express themselves without using words. And in many cases, art is the only way people can effectively express how they feel internally.

When Matisse was young he got sick: appendicitis. During his recovery, his mother gave him art supplies. For young Matisse, it was as if he could finally start to stumble across the desert’s plains and discover paradise was waiting for him on the other side. Art began to help in the healing process. A decade later was the birth of Fauvism, a period of art that used color boldly, wildly, and freely, like a wild beast or fauve in French.

Then, a few decades later, Matisse got sick again: cancer. Now too weak to paint or sculpt like he had been doing in his first life as an artist, his second life began thanks to a new technique: cut-outs. He was free to draw with scissors like a young kid – still bold and wild. In fact, Matisse said, “Only what I created after the illness constitutes my real self: free, liberated.” The art of creating cut-outs from his perspective gave birth to his true self — it gave his body life.

One of those cut-outs is Icarus. It is a black silhouette, with a blue background, has a red dot near the subject’s chest, and is surrounded by yellow stars. It’s simple, beautiful, and makes you wonder. I lean back from the table, take a bite of my chocolate chip cookie, look outside at the rain falling, and start to question the picture. Is the subject flying, falling, or dancing? Is it a symbol of ambition, hubris, or freedom? Perhaps it’s a warning like the common advice from the story of Icarus – don’t fly too close to the sun. Or perhaps it’s a celebration of those who dare to.

I’m no art historian so I can’t say for certain, but I think the dead giveaway is the red dot. The red dot is a heart — a sign of life. The figure is dancing, refusing to stay still but rather choosing to stay alive. The black silhouette is Matisse, but he designed it so that it could be anyone. The message is whether you succeed or fail, whether you fly or fall, no matter what, keep moving. Not just now, but forever. Not purely in the physical sense, but somewhere deeper than that. Like making art is deeper than words can express. To move is to be free. To create is to live. To keep moving, to keep creating, this is how you stay connected with yourself and with others. It’s how you stay in the dance.

I think Matisse’s life is a testament to that. It’s why he’s the main character on the cafe’s wall. When he was young, brushstrokes of bold color were his method to transform his pain. When he was old, cut outs did the job. Whether he was ascending or descending on his journey as an artist, he never stopped dancing. When I look around at the cafe, I see people’s spirits lifted by all of the colors, moving in every direction. Some chatting with friends. Some typing, working on this or that. Some writing in their notebook. It’s part of the dance inside of the cafe. It’s an art form moving in its own way. It was at this point that I started to feel like I understood why Matisse was the main character on the orangish wall, why it led me down such a rabbit hole, and why Dali wouldn’t blink until I got the message. This is the beauty of leaving your house every now and then and going to a cafe like Cokernut to eat and drink and write and think and people watch and all of that — it’s to join the dance of not just the cafe, but the city at large. To get out, move, and explore where you live. To know that there are messages everywhere, even inside orangish facades that you won’t miss when you drive by and on walls and on book covers, waiting for you, staring, screaming, “Look! Look! Don’t you see?”