Why would I eat ramen in Vietnam? This is a question I occasionally asked myself when I first moved to the city. After all, having grown up in Tokyo, I’d eaten my lion’s share of ramen already and though I loved the dish, I was more interested in sampling the array of Vietnamese noodle dishes on offer. Of course you had Phở—The world knows about Phở, but what about Bún bò Huế? That spicy, tangy broth filled with thick, chewy noodles and a delectable assortment of meats like beef, pork knuckle, and pork sausage? Then you couldn’t forget Hủ tiếu, Mì Quảng, and the rich, decadent crab based broth that is Bánh canh cua. But we’re only getting started. There’s Hanoi’s very own Bún Chả, there’s Bún Thịt Nướng, Bún Riêu, and Bún Cá. Then you’ve got the different types of Mì Xào, which in my eyes might be the perfect plate to accompany a night of drinking at any local nhậu. And the list goes on. So, once more, we have to return to my question: Why would I eat ramen in Vietnam? It wasn’t until I went to Aoya Ramen that I found a reason.

Sitting on the side of the road as a lot of the best things are in Vietnam, Aoya is a ramen stall that’s very likely the first of its kind in the country. Located on 30 Ngô Thời Nhiệm street in District 3, I visited a few Fridays ago with Oanh from The Demor. Upon arriving, I spotted Tung and Thuy from Neo-, who were standing and enjoying a few skewers, cooked up on a grill next to the ramen stall. Tung asked whether I’d been here before. I admitted I hadn’t to which he laughed, before telling me the guy who ran the place could speak Japanese and so I should speak to him.

The stall was packed on arrival so Oanh and I waited in a line on the side. It was a nice, quiet residential street, not the type of place you’d expect to find a ramen joint and yet Aoya sat right smack in the middle. Already it was hard not to be impressed with the whole operation. The stall reminded me of yatai (mobile food stalls) in Japan, and especially those in Fukuoka, a prefecture known around the country for the pride and reverence it places on the humble yatai. Dining at a yatai in Fukuoka is akin to having a slice of pizza in New York or a taco in Mexico—It’s part of the culture, it’s the quintessential representation of what it means to eat there. So waiting in line at Aoya and seeing the way the orange lanterns glowed against another evening settling on Saigon, watching the steam rise from bubbling pots where noodles were dunked and cooked, hearing Nujabes on the speakers, hearing the slurps of satiated customers—who at the end leaned back and pat their bellies—for a moment I got the sense I really was on some sidewalk in Fukuoka. On this street were dozens of other yatai, some serving kushiyaki, others motsunabe, more still oden, tempura, gyōza. The salarymen were out in flocks, toasting to the end of another long day, finishing half their Asahi in one gulp before looking around with something of a tired, resigned grin. We’d eat and drink and eat and drink, hopping from yatai to yatai as the night became one blur of food and beer and the occasional lemon sour or highball. And at the end of it we’d go home. Sleepy. Stuffed. Satisfied.

Space opened on a wooden table next to the counter. Oanh and I sat there. I went for a shōyu (soy sauce) base and she went for a shio (salt). I ordered a Sapporo as well—How could I not? The beer came in a nice, tall, ice-cold glass. I’d be hard pressed to find a lot else in the world that can put you in relaxation-mode as much as drinking a beer from a nice, tall, ice-cold glass. It puts you in the mood. And with Nujabes playing on the speakers as the three workers—two guys making the food, one lady serving the customers—did their jobs with the silence and skill of experts who’d been at it for years, the mood went even deeper. I knew I was in good hands.

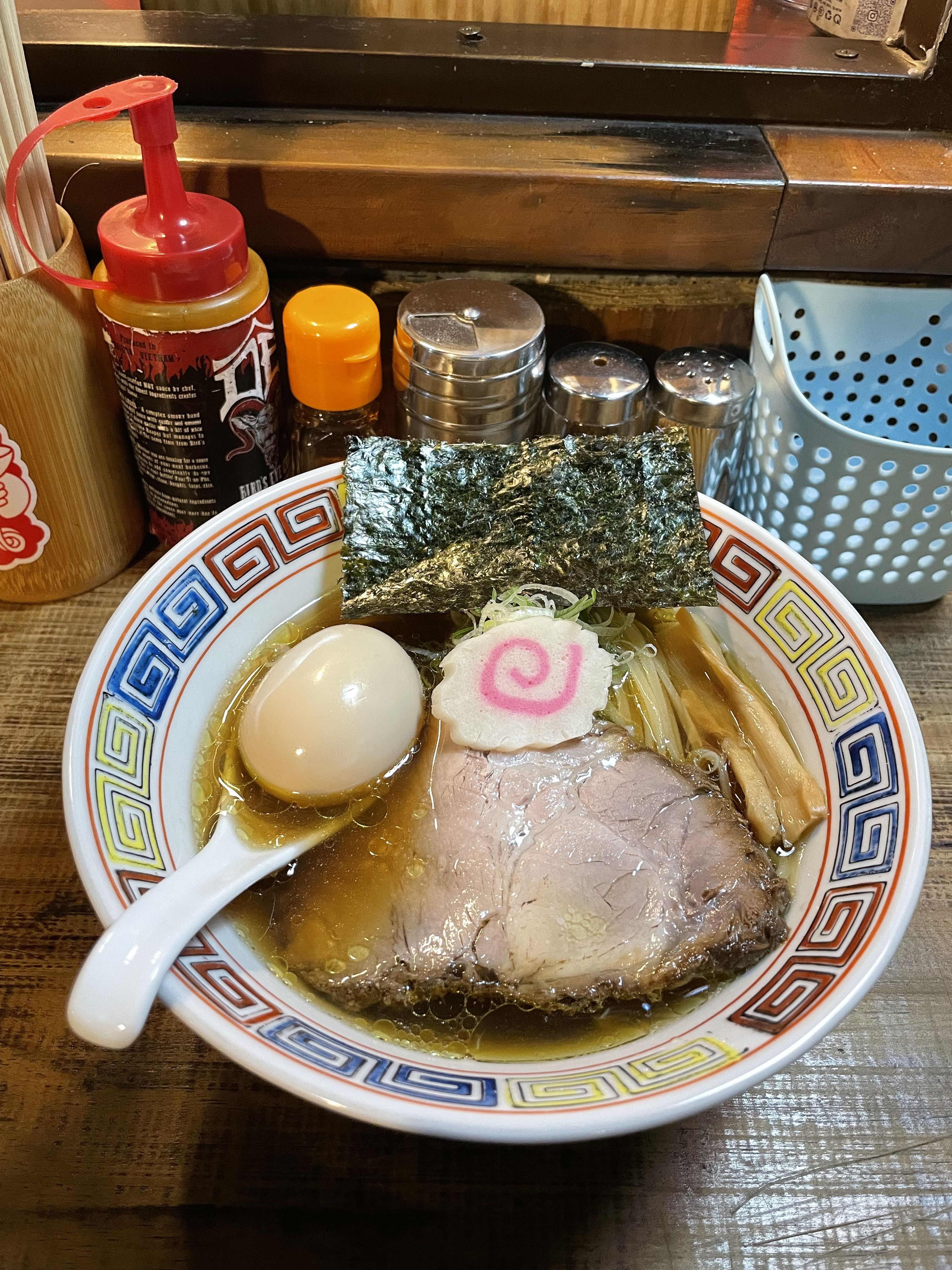

Our bowls were placed in front of us. The first test, a sip of the broth. Though it lacked the oomph I’d come to expect of shōyu ramen from home, there was a delicacy to its depth which I could appreciate. A slurp of the noodles: bouncy, chewy, exactly what I wanted. Oanh gave me some of her shio ramen, which isn’t typically a flavour I opt for when I’m on the hunt for ramen but Aoya’s was nice. Not overly salty. Clean, clear, just right. Besides the noodles and broth, our bowls came with all the traditional toppings: chāshū (braised pork), menma (fermented bamboo shoots), naruto (a cured fish paste with a pink swirl in the middle), spring onions, seaweed, and a boiled egg. I’ve heard it said by chefs that if you want to know whether someone can cook, have them make an omelet. I suppose then the boiled egg is ramen’s version of that—It has to be just right, neither over or undercooked but just at that point where the yolk is still creamy while the egg itself has some firmness, a bit of bite. Aoya’s, I’m happy to report, was spot on.

Before leaving I ended up chatting to the owner. He spoke Japanese well, and it was funny how the way he spoke Japanese reminded me of the way ramen-shop owners talked in Japan. There was a gruffness to the tone, a blue-collar earthiness about it that stripped away all formality and made you feel that while this person might not be someone you knew, he was just another person, nothing more. We paid our bill and left, and as we did I noticed a group of three Japanese guys waiting in line for a seat. Perhaps they’d been like me—they’d tried all the phở, bún bò, and mì xào they could and now they figured why not, why not a taste of home? Or maybe they’d been coming here for a while already, always happy to wait in line for a seat. And so to the question I’d posed earlier they might—if I’d asked—have a simple answer. Why eat ramen in Vietnam? Because of Aoya. That’s why.

- Find Aoya Ramen

- Follow Aoya on Instagram